| The selling off of people’s commons – The case of Greece

by Marica Frangakis[1]

Auf dem Markt in Athen, Foto: Ed Yourdon

In the 1980s, and especially in the 1990s, the European countries went through a phase of privatization, which radically reduced the reach of the post-WWII welfare state. The rationale for such an exercise varied, as did the forms of privatization across sectors, countries and time. Irrespectively of such variations, however, privatization has been described as “… a stage in the evolution of capitalism … (representing) a shift in the relations between the state, society and the economy which is a pervasive process in political, social and economic terms” (Frangakis et al, 2009:10)[2]. The public debt crisis has deepened this shift in favour of private sector interests, as the Greek experience amply demonstrates.

More specifically, privatization is one of the conditions on which the first bail-out was granted to Greece in May 2010. The Economic Adjustment Programme, accompanying the bail-out, contains a detailed privatization plan by type of asset, mode of sale and expected sales proceeds over the period 2010-2015, the time span of the Programme. A target of proceeds equal to €50 billion has been set.

Although a late comer, as privatization gathered speed in the late 1990s, Greece carried out extensive privatization programmes in the past, placing it quite high amongst other European countries. In this sense, the current thrust is a determined attempt to sell off what remains of the Greek people’s commons.

Furthermore, the new phase of privatization, as shown by the Greek experience, as well as by the experience of other EU member states undergoing EU/IMF programmes, points to a significant shift in EU policy. In particular, the EU seems to be departing from its traditionally neutral stance with regard to ownership, as clearly stated in the Treaty of the Union, towards a stance that favours privatization, not only as solution to the public debt crisis, but also as a means of increasing the competitiveness of the economy. Neither of these claims is substantiated by past experience, nor are they grounded on any particular study of the sector/country currently involved. In this sense, they are but expressions of the political and ideological viewpoint of the European elites and the interest groups these are associated with.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

- Section 1 reviews the privatization of experience of Greece prior to the public debt crisis;

- Section 2 examines the current privatization plans;

- Section 3 assesses the implications of the current privatization exercise for the Greek economy and for society, as well as more generally for the European context.

- Section 4 concludes by taking a broader view of the prevailing narrative and the need to change it in order to defend the people’s commons.

1. Background and history of privatization in Greece

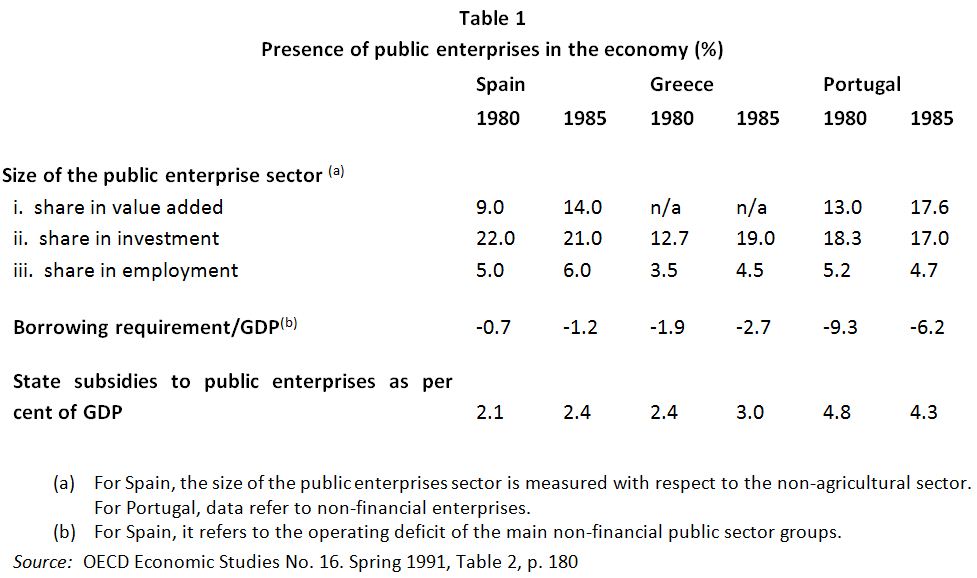

Greece underwent a number of nationalization waves in the 20th century. Schematically, there have been (i) a “developmental” wave (1950s & 1960s), aiming at supporting the country’s industrialization process; (ii) a “democratization” wave (1970s), occurring at the end of the military dictatorship in 1974 and signifying the return to democratic rule and (iii) a “socialist” wave (1980s), aiming at rescuing a large number of over-indebted firms (Pagoulatos, 2005)[3]. Thus, by the mid-1980s the presence of public enterprises in the economy was quite strong in Greece, comparable to that in Spain and Portugal (Table 1).

Privatization followed the reverse order, starting with the latest enterprises to have been nationalized and moving to those nationalized in the 1950s and 1960s.

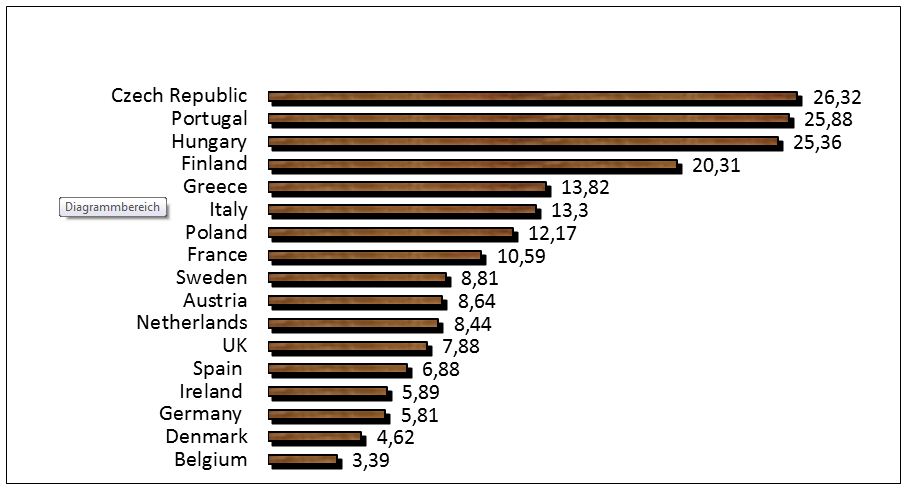

Greece was a late comer on the privatization scene. Between 1977 -1992 the proceeds from the sale of public assets in Greece amounted to 1.19% of the corresponding proceeds of the former EU15, increasing to 2.85% over the period 1993-2007. As it has been noted, Greece, like other smaller economies, such as Finland and Ireland, made ‘relatively huge efforts to privatize’ (Clifton et al, 2006:744)[4]. Indeed, over the period 1977-2007, the privatization proceeds amounted to nearly 14% of GDP, placing Greece in fifth position amongst 17 EU member states, as shown in graph 1 below.

Graph 1 – Privatization proceeds as % of GDP (1977-2007)

Source: Privatization Barometer; OECD; author’s own calculations

2. Privatization as a ‘structural reform’

An extensive privatization programme is one of the conditions on which Greece was granted a bail-out, where this is considered to be ‘a crucial instrument to support growth and fiscal sustainability’ (EC, 2011:28)[5]. More specifically, according to the European Commission, “The Greek government is one of the European sovereigns with the richest portfolio of assets. This portfolio includes listed and non-listed companies, concessions and commercially viable real estate (buildings and land). … Privatizing those assets will contribute to reduce debt with a small, if any, cost in terms of future revenue. At the same time, privatization promotes the economic activity and foreign direct investment” (ibid:2).

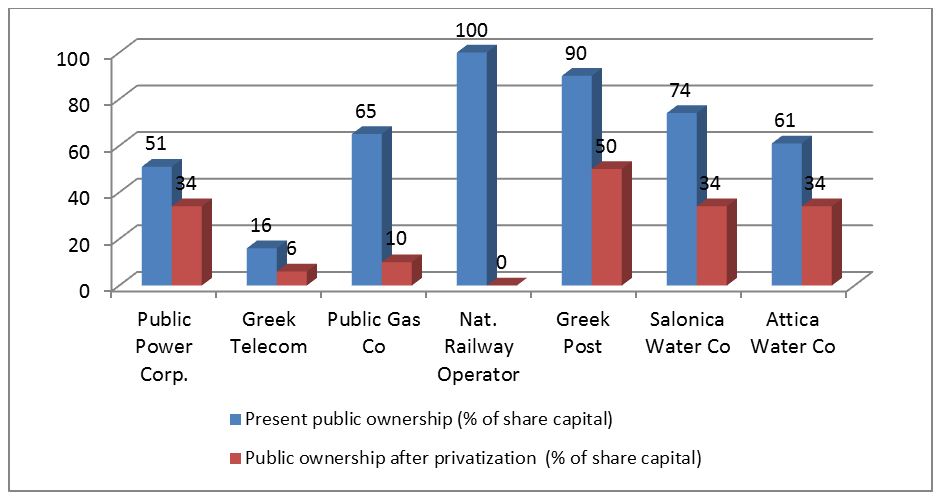

To this end, a long list of public assets has been specified, including telecommunications, transport, energy, water provision, the country’s main ports, the Athens airport, banking, postal services, motorways, real estate, lotteries, etc. Most of these enterprises were already partly privatized in the past. Following the new privatization wave, the share of public ownership is expected to be either extinguished altogether, or radically reduced. The following graph shows the reduction in the state presence in a number of public utilities. It is indicative of the expected outcome of the present privatization assault on public ownership.

Graph 2 – State ownership of public utilities before & after the current privatization plan

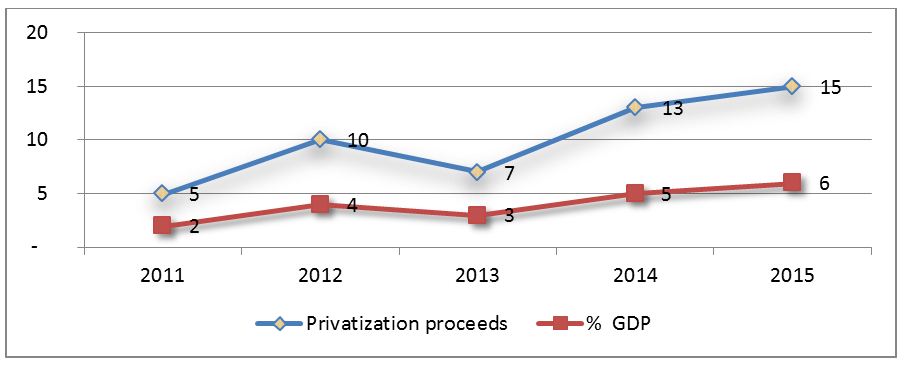

An overall target of €50 billion worth of privatization proceeds over the period 2011-2015 has been set, as well as annual targets, as shown in the graph below. In relation to GDP, the overall target for the five year period – set at 20% of GDP – by far exceeds the historical record of privatization proceeds over the thirty year period, 1977-2007, which amounted to nearly 14% of GDP! This is indicative of the size of the privatization exercise imposed on Greece by its creditors, as well as of the fire-sale type of privatization envisaged.

Graph 3 – Privatization proceeds: targets for 2011-2015

Source: EC, 2011, The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, Fourth Review, Spring 2011; author’s own calculations

In 2011, the first year of the programme’s implementation, the total amount of €1,558 million was obtained from the sale of public assets, including OPAP licensing – a football betting company, set up in the late 1950s, to help finance infrastructure works – a license extension of the mobile telephony spectrum and four aircraft. This sum was below the €2 billion target for the year. Thus, it is now admitted that the implementation of the privatization plan will take longer than initially envisaged, although the overall target has not been altered[6].

The on-going privatization plan is to be carried out by a privatization fund especially set up along the lines of the Treuhandanstalt trust agency, which undertook the privatization of the East German state-owned assets in the early 1990s. According to the Economic Adjustment Programme, such a fund is expected to be “independent and depoliticized”, insofar as it will be staffed by people from outside the public sector, while two observers nominated by the Commission and the Eurogroup will be included in the board (EC, 2011:31).

The Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund was indeed established on 1st July 2011 (Law 3986) with a share capital of €30 million, while it began its operations in August 2011. Already, a long list of public assets have been transferred to the HRADF. According to its First Quarter Report (1/7/2011-30/9/2011), a staff of nearly 30 persons has been appointed, while the Fund’s expenses amounted to €135,413 and its revenues to €61,495 in the first three months of its existence.

3. Implications of the current privatization drive in Greece

The current privatization drive taking place in Greece raises a number of issues of broader applicability. First, a shift in the position of the European Commission viz-a-viz ownership appears to have taken place. Second, the belief that the sale of public assets makes a positive contribution to public finances perpetuates a fallacy. Third, the way in which it is conducted denotes a limitation of sovereignty, as well as the denunciation of democratic control. Fourth, it violates human rights, especially of the most vulnerable segments of society. Fifth, the whole exercise will benefit capital, whether Greek or multinational, at the expense of Greek workers and of society at large.

We shall examine each of these issues in some detail.

- According to article 345 of the Treaty of the Union, “The Treaties shall in no way prejudice the rules in member states governing the system of property ownership” (ex. Art 295 TEC). However, the enthusiasm with which the European Commission has endorsed privatization as a vital condition for the bail out of Greece and its firm belief that this will benefit both public finances and the competitiveness of the economy reveals a shift in its position, to the extent that it makes it contextual. Even though, the neoliberal transformation of the EU in the 1990s strongly influenced the privatization drive of the period, the Commission has traditionally been careful not to favour privatization openly. This seems to be changing.

- Further, the belief that privatization reduces a country’s public deficit and debt conceals a fallacy. As Daniel Gros has argued, “large-scale privatization to reduce short-term debt (by paying maturing bonds in full) will actually increase the risk premium on longer-term debt” (Gros, 2011:1). This is because “the value of the remaining privately held (long-term) public debt must surely decline because in the absence of default the upside for creditors is limited (by the face value), whereas the downside will become worse in case of default.” (ibid). Thus, asset sales reshuffle claims among different creditor groups, rather than making the return of the indebted country to the capital market any easier or quicker[7].

- Similarly, the claim that privatization will increase the competitiveness of the economy and growth is not founded on any specific study of the assets being privatized. While to the extent that most of these concern utilities and other natural monopolies, privatizing them is likely to increase monopoly profits, rather than growth[8].

- Furthermore, the experience of the Treuhandanstalt agency was a negative one. During its existence (1990-1994), it sold about 8,500 business enterprises that originally employed four million workers. By the end of the process, 2.5 million workers were out of jobs and the agency itself, which was expected to turn a profit, wound up more than $400 billion in debt. The experience of the HRADF is likely to be similar, in view of the time pressure and the haphazard way in which privatization is taking place.

- In July 2011, Eurogroup President Jean-Claude Juncker stated that the austerity measures imposed on Greece – and privatization is part of that package – will result in “the sovereignty of Greece being massively limited”[9]. However, the rulers of Greece have gone even further in denouncing the process of democratic control itself! Thus, in the Letter of Intent addressed to Ms. Christine Lagard, the IMF Managing Director, dated February 2012 and signed by the Prime Minister, Lucas Papademos, the Deputy PM and Minister of Finance, Evangelos Venizelos and the Governor of the Bank of Greece, George Provopoulos, it is stated that “we remain committed to a process insulated from political pressures”[10]. Similar assurances have been given in writing by the leaders of the two major parties, the socialists (PASOK) and the conservatives (New Democracy). Such political assurances were a condition for the second bail out in 2012.

- Large scale, fast track privatization, without due concern for its social implications, undermines the human rights of the population. As the United Nations independent expert on foreign debt and human rights, Cephas Lumina, has warned “The implementation of … austerity measures and structural reforms, which includes a wholesale privatization of state-owned enterprises and assets, is likely to have a serious impact on basic social services and therefore the enjoyment of human rights by the Greek people, particularly the most vulnerable sector of the population such as the poor, elderly, unemployed and persons with disabilities”[11].

Overall, the privatization drive currently taking place in Greece is going to produce social hardship, not countervailed by any economic benefits to society at large. On the contrary, such benefits as may be derived will favour the buyers of these assets, rather than the Greek economy. These are disquieting signs, especially in the European context, to the extent that a clear preference for private property and control is being manifested by the EU authorities.

4. Need for a different narrative

In early 2009, before the public debt crisis erupted in Greece, the late Professor Jorg Huffschmid noted that: “As long as the underlying causes of the over-accumulation of financial assets is not addressed, the pressure will remain to organise ever higher profits for these assets. … In this context the pressure for privatization opportunities may even become sharper than before”[12] (Frangakis et al, 2009:58-59). The Greek case proves his point clearly!

The narrative on which the austerity measures were imposed on Greece, as conditions for the loans given to it, is one of ‘living beyond one’s means’ and therefore deserving to be punished on a long-term basis[13]. The extensive privatization of public assets is part of such a punishment.

This view conveniently ignores all other factors inherent in the indebtedness of the non-core EU countries, such as the missing links of the euro architecture, the mercantilistic policies on core countries, such as Germany, and the role of finance in a deregulated environment. In this way, it deflects the pressure for change in all of these areas.

As discussed above, the on-going privatization of the remaining public assets in Greece will make a small impact, if any, on the public debt, while it will not increase the competitiveness of the economy. In a longer-term perspective, it is likely to impoverish both the economy and society. The winners are going to be those acquiring Greek assets at rock-bottom prices and those gaining entry into monopoly sectors.

Overall, it is imperative that there is a change in narrative. Attention has to shift back to the fundamentals of the crisis, to the role of finance both globally and in Europe, to the incomplete project of European monetary unification, to the requirements of an economically developed, socially cohesive, ecologically sustainable and democratic European Union. In such a perspective, the selling off of people’s commons has no place. On the contrary, such commons need to be defended and further developed for the sake of future generations, whose interests must be taken explicitly into account.