| From #MeToo to #WeStrike. A Politics in Feminine

A year before #MeToo erupted in the United States, women in Argentina were fighting against an epidemic of violence against women in which, on average, one woman was killed every thirty hours. At noon on October 19, 2016, thousands of women all over the country walked out of their jobs and stopped doing unpaid housework, as well as carrying out the emotional work required of political organizing. The strike was Argentinian women’s response to the growing number of femicides in the country, and specifically to the brutal murder of the young Lucía Pérez. But in their call to strike, they connected the many forms of violence that women experience in an economic system based on their oppression and exploitation:

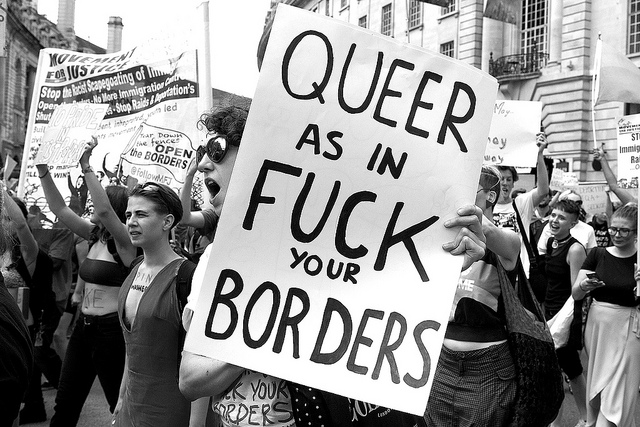

»Among women under thirty years of age, unemployment is at 22%. Our lives are precarious. Women regarded as sluts sent to prison. Trans women are daily repressed in the streets while their right to join the working world is not guaranteed, leaving prostitution as their only option. Women murdered by their partners or for a job. Abused by their parents or beaten by the police. We are experiencing a hunting season. And neoliberalism tests its strength against our bodies. In every city and every corner of the world. We are not safe.«1

Half a million women in Buenos Aires went out onto the streets on that October 19th, expressing their outrage and their determination, and, in the process, opening a space for building women’s collective strength. Participants emphasized the importance of telling their male partners and comrades, »we are not here for you today«, doing only the work that was necessary to be together with each other, with estamos para nosotras as their slogan.

The strike made visible the myriad forms of labor that women carry out on a daily basis; their refusal functioned as a map of the labor women do – paid and unpaid, formal and informal, in the household, the office, the school. It brought different women together, despite their differences, enabling them to recognize both the similarities and the differences in their everyday practices, their forms of labor, and their exposure to violence.

A few months later, millions would take to the streets in the United States against the openly misogynist new president. The Women’s March, despite some of its liberal leanings its purely institutional understanding of politics, its focus on a narrow set of issues and a narrow definition of »woman«, and its emphasis on Trump rather than the longer term and structural factors behind women’s oppression – was an important experience for the many women who started to question assumptions about the supposedly post-feminist world we live in, as well as the agenda of neoliberal or lean-in feminism. If we supposedly have gender equality, then how could a man who openly brags about assaulting women have become president? From these questions, many began to think about their own experiences of inequality, of discrimination, and violence. For many women, it was also their first experience of mass collective action.

As a group of mostly university professors and students, many of them Latina migrants in the United States, argued during the first Argentinian strike:

»We felt that it was important to stand up in solidarity and soon realized that we also wanted to make visible (…) a form of violence that happens in the U.S. as well. For instance, the day of the strike, students — Black, white, and Latina — began recounting their own experiences of microaggressions and violence in the U.S, of being harassed on the street and at work and at school (…) As we can see, the violence in Latin America does not seem so far away. We are connected through a shared set of experiences. In a country like the U.S. where news about gender-based violence is dominated by stories about rapists not facing repercussions, and in universities where one in every six women is sexually assaulted, women started to ask: What would happen if we went on strike too?«2

The viralization of #MeToo adds to this growing global organization of women. The spread of the hashtag and the narratives accompanying it were powerful not only for making visible harassment in every industry and in every space, but also as an action through which women could find a collective voice. However, many felt ignored or left out by the focus on certain industries and deserving subjects. The #MeToo movement is thus at its weakest when it is limited to individual denunciations made by famous women, or focusing exclusively on institutional action and change.

What can the #MeToo movement learn from Latin American feminists? How can a global perspective help develop new insights into forms of violence and create a politics that challenges the fundamental basis of gender inequality?

Popular Feminisms in Latin America

Women in Latin America have been organizing collectively to fight against gendered violence for many years. The bordertown of Ciudad Juárez became a flashpoint for the struggle against femicide, as activists faced the neoliberal laboratory of the maquiladoras: On the one hand, American companies seeking cheaper labor across the border, on the other hand a new class of young women, migrants, seeking freedom in paid labor away from the confines of family and community. Since the implementation of NAFTA, hundreds of these women have been disappeared, tortured, and/or murdered, while the perpetrators of those crimes generally go unpunished. Most investigations point to a network of complicity between patriarchal state institutions, local law enforcement, drug traffickers, and factory bosses seeking docile workers.

It was the quests for justice led by family members and friends of the murdered girls and women, that initially brought attention to the issue of femicide in Latin America. That these women and girls were mostly poor factory workers, students, and proletarians in the informal sector, and that their disappearance was initially ignored by the government, the press, and most academics, is not a fact that should be forgotten. The movements that formed in response therefore emphasized the relationship between the brutal violence against women and girls and Ciudad Juárez’s position in a globalized production system, directly linking the murders to gendered economic exploitation.

Further south in 2014, Ni Una Menos (NUM) formed as a response to the increasing rate of femicides in Argentina and the lack of institutional response. Both an organizing collective comprised of journalists, writers, artists, and academics, and a larger movement made up of women from diverse class backgrounds, NUM has been organizing a number of large mobilizations over the last two years, along with two women’s strikes. The first national action included a public reading, including art and poetry. The following year, larger open assemblies and a large march in June preceded the first women’s strike in October. This momentum carried over into 2017, with the women’s strike on March 8 and plans for another strike in 2018. The power of Ni Una Menos has reframed the debate about gendered violence and women’s work and contested gender relations at multiple scales.

Ni Una Menos builds on a long history of women’s organizing in Argentina, especially the annual National Women’s Meeting and the movement to legalize abortion. The National Women’s Meeting, which has been held in different cities across the country since 1986, drew approximately 70,000 women to Rosario in October 2016. These meetings are self-organized, horizontal, open gatherings to discuss a variety of issues, from reproductive health to domestic violence to discrimination in the workplace. They bring together women from different regions of the country, and from different political and ideological as well as class and ethnic backgrounds. While women from political parties and some unions were already participating in the meetings, it was when women from organizations of unemployed workers began to attend that the class character of these meetings shifted considerably. Debates about abortion from a human rights perspective were suddenly transformed when women living in slums began talking about friends who had died from unsafe and clandestine abortions.

These experiences reflect a certain type of popular feminism, which has only recently taken hold in working-class neighborhoods. On the one hand, it emerges from the frustration that women experienced who were participating, for example, in the movements of the unemployed, the workers’ cooperative movements, or other populist and leftist struggles, where they have been doing the important everyday organizing work but were rarely in leadership positions and continued to experience violence from their »comrades.« Many of these women had collectively organized to ensure the survival of their families and communities during the worst of Argentina’s economic crisis and therefore were not likely to passively accept these mistreatments. They began to call out and publicly denounce male aggressors, in ways similar to #MeToo, but also to turn those political spaces into sites of building women’s collective power.

Some of the most marginalized and precarious workers in Argentina play a leading role in this feminism from below: street vendors and informal stallholders, textile workers in clandestine workshops or at home, workers in cooperatives, recipients of government benefits, and other workers in the informal sector. Together these sectors are understood as the popular economy and the workers are collectively organized in the Confederation of Popular Economy Workers (CTEP). While most of the major unions in the country were resistant to the idea of the women’s strike, CTEP was one of the organizations most supportive of both women’s strikes. Because of their precarious position –missing just one day of work could mean not being able to feed their family that day – these workers run unique risks in participating in a strike action. Yet, they were one of the first groups to endorse the strike and participated heavily in the event, recognizing that the popular economy is largely made up of women and that these women are more likely to experience the full continuum of gender-based violence.

This multiplication of feminism in different spaces has broadened the focus of feminist activism. From ever urgent demands for reproductive rights and equality in the formal workplace and formal political sphere, new demands arise connected to everyday forms of violence and precarity. This addresses questions of the reproduction of life itself – recognizing the multiple ways that contemporary capitalism attempts to directly extract value from life and, in doing so, puts that life at risk.

A Collective Subject is Born

Drawing on the these Latin American feminist movements, we should ask how the abuses of power identified by #MeToo are part of a larger constellation of violence and coercion. Is it possible to find a common cause between low wage, mostly Black and migrant university housekeepers facing an abusive manager, and female students on the same campus facing high rates of sexual assault?

Common ground cannot be assumed a priori but that does not mean that it cannot be created. One of the most insidious elements of patriarchal oppression is having been taught to blame ourselves for our experiences of abuse and to not speak about what happens to us. #MeToo has opened a space for challenging that atomizing silence, demonstrating not only how widespread violence is, but also its structural nature. To challenge the very foundation of gendered violence, we must learn to make these connections.

In a statement released on January 8, 2018, Ni Una Menos attempts this in their call for an international women’s strike,

»Because this tool allows us to make visible, denounce, and confront the violence against us, which is not reducible to a private or domestic issue, but is manifested as economic, social, and political violence, as forms of exploitation and dispossession that are growing daily (from layoffs to the militarization of territories, from neo-extractivist conflicts to the increase in food prices, from the criminalization of protest to the criminalization of immigration, etc.)« 3

Largely, these connections have been made through the practice of assemblies, where women share stories of facing sexual harassment, of being afraid to advocate for better working conditions, of staying in abusive relationships. A woman shares a story, another woman relates and adds her experience, another woman, maybe one working as a domestic employee, doesn’t feel included in the narrative and objects, adding another layer to the analysis. The differences between experiences are neither erased nor ignored, nor are they considered insurmountable. Through the assembly, through the process of working out common language and taking to the streets together, a new collective subject is born.

Assemblies multiply in diverse spaces: in workplaces, in unions, in political organizations, in schools, in urban neighborhoods, towns, and rural areas. There are assemblies of artists and writers, of musicians, of teachers, of migrants. Other assemblies bring together two or more different groups to facilitate dialogue and collaboration. For example, an assembly between Ni Una Menos activists from around the country and indigenous Mapuche activists in El Bolson brings women together under the slogan of »our bodies, our territories.« In this way, the commodification of land and natural resources is connected to the exploitation of women.

Women’s assemblies occur within unions and among laid off PepsiCo workers fighting for their jobs. In Buenos Aires, the slogan »We want ourselves debt free« is a play on one that originated in Ciudad Juarez, »We want ourselves alive.« The statement accompanying the action proclaims: »Finance, through debt, constitutes a form of direct exploitation of women’s labor power, vital potency, and capacity for organization. The feminization of poverty and the lack of economic autonomy caused by debt make male violence even stronger.« Financial precarity and gendered violence are interrelated, in both theory and practice.

At the heart of all this violence, these various women’s groups argue, is the devaluation of women’s reproductive labor and a systematic attack on reproduction. This attack plays out in multiple arenas, from the renewed defense of the heteropatriarchal family model by right-wing governments around the world and neoliberal austerity’s cuts to state support for social reproduction, to attacks on reproductive rights and direct violence against women’s bodies.

As Silvia Federici so importantly showed us, this violence is not new; it lies at the heart of capitalist accumulation, constituting its original and repeated violence. This means, in turn, that the autonomous organization of women to collectively ensure their reproduction poses a threat to capital, threatening the separation of workers from their means of reproduction, which underlies capitalist accumulation. Violence against women’s bodies has what Rita Segato has termed a »pedagogical« or disciplining effect, creating obedient subjects beyond the individual targets of violence. Segato argues that this is an essential element to maintaining colonial and capitalist power arrangements in general by discouraging any type of resistance to dominant power relations.4 Today, as capital seeks to broaden its methods of extracting value from reproductive labor, the very reproduction of life is put at risk. It is the networks and communal ties that women have long organized and relied on that begin to break down with this expansion of capital accumulation based on finance, making women increasingly vulnerable.

As Latin American feminists conceptualize the links between forms of violence, they are also mapping contemporary forms of exploitation and drawing a new map of class composition. In so doing, they identify new opportunities to forge alliances: »In the two Women’s Strikes that we organized in less than a year, together with women trade unionists and all types of organizations, we were able to put on the agenda and assemble the demands of formal workers and the unemployed, of popular economies along with the historical demand for the recognition of the non-remunerated tasks that women perform, and of politicizing care work and recognizing self-managed work.« 5

By starting from the different ways in which value is extracted from women’s labor and violence visited on their bodies, these activists describe a capitalist system founded on and sustained by violence against women.

A True General Strike

From this work of connection, the women’s strike emerged. As NUM explained in their statement calling for the March 8 International Women’s Strike: »Using the tool of the strike allowed for highlighting the economic fabric of patriarchal violence. And it was also an enormous demonstration of power because we removed ourselves from the place of the victim to position ourselves as political subjects and producers of value.« 6

Or, as Verónica Gago says speaking of the October strike: »The strike managed (…) to connect violence against women with the specific political nature of the current forms of exploitation of the production and reproduction of life. This produced an impressive effect. First, because it broadened the idea of the strike. We started bringing together women from all different sectors, waged or not, young and old, employed or unemployed. This really caught on and activated people’s imagination about how to multiply the effectiveness of the tool of the strike. What does it mean to strike in your position? If you are not unionized, but also if you are in an organization (in school or a community network, for example) and so on.« 7

The women’s strike, as carried out at distinctive sites across Latin America in October 2016 and globally on March 8, 2017, was thus about centering women’s labor, but it was also about the economic and political function of gendered violence.

Yet, despite its global reach, critics were quick to argue that the women’s strike was not a »real strike« because it did not follow the strictures or forms of strikes past. But how could it? As Mariarosa dalla Costa plainly wrote in 1974, »no strike has ever been a general strike. When half the working population is at home in the kitchens, while the others are on strike, it’s not a general strike.«While perhaps today we have seen more than men in big factories go on strike, it still stands that we have never seen a truly general strike. The Madrid-based collective Precarias a la Deriva made that point clearly when they asked, of women and precarious workers who were unable to participate in a general strike called by Spanish unions, »what is your strike?« Their collective inquiry mapped the difficulties precarious workers faced in participating in the national action without losing solidarity with the action itself. Instead, this insight was a starting point to expand the idea of what a strike could be, drawing from an expanded vision of what work is. The strike became an »everyday and multiple practice« that takes place across a range of spaces from the street to the household.8 In other words, the women’s strike is inseparable from the very practice and process that makes the strike possible, it opens up a new practice and time. »We women are reclaiming our time, to no longer do what is imposed on us, but to do what we want. To find ourselves, think together, speak up, occupy the streets, the plazas, appropriate public space and turn it into a space of hospitality and free circulation for ourselves.« 9

A Politics in Feminine

In a video supporting the 2018 Women’s Strike, Silvia Federici explains that »striking means not only interrupting certain labor activities, but it also means committing ourselves to activities that are transformative, that in a certain sense take us beyond our routine concerns and everyday life and that contain in themselves other possibilities.«10 What are these other possibilities that we might find if we stopped, for a day, reproducing gendered hierarchies and gender roles? #MeToo has made it clear what we are against. But what are we fighting to create?

Looking before and beyond the women’s strike, we see the emergence of a tendency that Raquel Gutiérrez has called a »politics in feminine.« This is not tied to essentialist notions of women’s abilities, but rather to one rooted in the unique perspectives and collective capacities of those charged with protecting and reproducing life. It is not referring merely to female participation in political activity or making demands in »women’s interests«. A politics in feminine refers to a way of doing politics differently, a way that seeks to overturn the social relations at the heart of capitalism, to change everything.

A politics in feminine ensures that social reproduction is our collective responsibility – a goal that necessarily increases women’s political power and targets capital accumulation. While at times engaging state power, importantly Gutiérrez’s concept is not defined by accessing or taking state power. Its politics do not contort itself into demands that are legible to the state but grow and take shape according to its own logic. In Gutiérrez’s words, a non-state-centric politics »is strengthened by defense of the common, it displaces the state and capital’s capacity for command and imposition, and it pluralizes and amplifies multiple social capabilities for intervention and decision-making over public matters.« 11

»To be victims,« Verónica Gago writes, »requires faith in the state.« Politics in feminine refuses victimhood. Instead, its strength lies in what various feminist activists have called among women, or practices of everyday self-organization allowing not only for discussing shared experiences, but also for something akin to consciousness-raising. Here, all women and their different experiences and knowledges are valued, leaving no room for superstars, whether actresses or academics. In networks of interdependence among women skills and relationships are developed that allow them to challenge the norms of power.

More than a politics of survival, a politics in feminine is built around desire, around women’s desire, and in direct opposition to a form of politics that conceives of militancy in terms of self-sacrifice and suffering. Its goal is to enhance the spaces for women’s joy and desire to flourish. #MeToo can open the space, not for a »sex panic« as some critics would have it, but for a politics premised on desire. The desire not to be harassed or attacked as well as the positive desire to assert our bodily autonomy, to move freely about the city and between states without fear, to build our own lives and own relationships in ways that do not reproduce the given gendered hierarchies. As Ni Una Menos stated in their call for the first International Women’s Strike in 2017, »Because #WeWantOurselvesAliveAndFree we risk ourselves in unprecedented alliances. Because we appropriate time and we create availability for ourselves, we make being together a relief and conversation among allies. Of assemblies we make demonstrations, of demonstrations celebrations, of celebrations a common future. Because #WeWomenAreHereForEachOther, this 8th of March is the first day of our new lives.« 12

#WeStrike

What will it take to move from #MeToo to #WeStrike? I can only offer a few suggestions: first, we must emphasize the collective element of our experiences of harassment, abuse, assault, discrimination, and oppression. We must turn #MeToo into a process of investigation, into a collective charting of how different women are situated in colonial-capitalist-patriarchal power. And through this mapping, construct concrete relationships of resistance and alliance, where we are figured not as victims seeking redress but as active political subjects. In order to enact lasting, systematic transformation, to change everything, we cannot fall into the trap of politics as usual, a politics of victims, a politics centered around the state. It means a politics in feminine, valuing the creativity that emerges from time and space among women.

As the Latin American movements have shown, it is in the practice of this politics in feminine that a new collective subjectivity is born. It is not our experiences of violence that defines who we are, but our struggle against violence that defines a collective we.

This article first appeared in (c) Viewpoint Magazine. We publish a slightly shortened version.

Notes

1 Ni Una Menos Statement, October 19. A collection including this and other statements from Ni Una Menos, Argentina is forthcoming in the journal Critical Times. See: directory.criticaltheoryconsortium.org/critical-times.

2 Erika Almenara, Ivonne del Valle, Susana Draper, Ludmila Ferrari, Liz Mason-Deese, and Ana Sabau, »We Strike Too: Joining the Latin American Women’s Strike from the U.S.«, Truthout, October, 2016.

3 Ni Una Menos Statement, January 8, 2018.

4 See Rita Segato, La guerra contra las mujeres. (Madrid, Traficantes de sueños, 2016).

5 »Desendeudas nos queremos,« Ni Una Menos Collective, June 2, 2017.

6 Ni Una Menos Collective, »How Was the March 8 International Women’s Strike Woven Together?«, Viewpoint Magazine, February, 2017.

7 Amador Fernández-Savater, Marta Malo, Natalia Fontana and Verónica Gago, »The Strike of Those Who Can’t Stop: An Interview with Verónica Gago and Natalia Fontana«, Viewpoint Magazine, March, 2017.

8 Precarias a la Deriva, »A Very Careful Strike: Four hypotheses«, Commoner, N. 11, Spring/Summer 2006.

9 Ni Una Menos Statement, November 25, 2016.

10 Gago, »Bloquear y transformer.«

11 Raquel Gutiérrez Aguilar, Horizonte Comunitario-Popular. Antagonismo y producción de lo común en América Latina. (Cochabamba: Sociedad Comunitaria de Estudios Estratégicas y Editorial Autodeterminación, 2015, pp. 89).

12 Ni Una Menos statement, March 8, 2017.